The Map is Not the Territory

Portland Art Museum – Portland, OR

Only moments after walking through the familiar doors of the Portland Art Museum I was immersed in a sea of lights and flickering shadows. Huge projections danced on sheets of fabric that hung across one of the museums’s tall-ceiling rooms. I watched, my neck craning up, up, up to find the source of the silhouettes of people that walked across the walls. I wondered if these blurry forms were taken from camera footage, perhaps from somewhere near the entrance. I moved around and waved my arms, but I could not see my shape in the ghostly images. Now that I reflect upon it, it’s funny that I was so eager to be under surveillance just so I could be a part of the exhibit.

A far smaller screen soon caught my eye from the corner of the large space. I entered a theater with a low ceiling and saw that the far wall had a projection of scenery from the Pacific Northwest with words that were small and difficult to read scrolling across the film. A male voice narrated a story in a native tongue, and I assumed the scrolling words were the translation. While the few other visitors in the room left in confusion and boredom, I noticed that if you blocked the projection of the scenery, the scrolling translation became clear and easy to read.

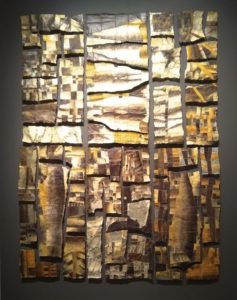

My eyes adjusted painfully as we entered the next room–a wide, open space with plenty of lighting. To my right, a collage of rock slates covered the wall, some formed into the shape of what I interpreted as a stegosaurus’s spine. Upon closer inspection of the wall piece, I realized that it was actually a collage of fish skins sewn together. The faded, tanned colors of the scales looked so similar to the other rock sculptures that they blended together into the same dry material. The whole thing looked like an archaeological exhibition.

Adjacent to the fish skins and slates was a collection of fruit-like sculptures made from recycled bits of garbage. Though their dun colors blended with the previous artwork, there was something dirty and unsettling about them. The fish wall had turned death and decay into an optical illusion, it had turned something discarded into something fascinating. I admit that the garbage fruit did no catch my attention in such a way. Tall, vibrant murals of gardens and jungles followed the mud and plastic, giving me calm release from the gritty colors that nagged my eyes.

The murals were followed by a series of sculptures that I can only describe as mud turtles. They did not have all the definable features of the animal, but their general shape evoked a sense of hard-shelled creatures emerging from a deep slumber, thick with sludge and soil. Their placement in the exhibition was pleasing as they seemed to be coming right out of the cheerfully painted gardens. The turtles headed towards a series of woven rods with what seemed to be human hair coming out of the top of each one. At a distance, they resembled strange wheat or thin cobs of corn, another trick on the eyes. Tall wooden staffs carved into points at the end followed the rods, and I thought about how humans modify nature to fit their own means, a theme I noticed was recurring.

At the center of the hall was a sculpture I had already seen on the Museum website–smooth rocks that resembled pebbles but were larger than my head hanging in mid air, suspended by invisible wire and completely still, even with the breeze of visitors bustling by. They looked as if they could fall at any moment, as if time had paused while a God cast them onto the earth. As simple as they stones were, I could have stared at this piece for endless minutes. The title made me smile, Moving Mountains.

As I mentioned earlier, much of the exhibit reminded me of archaeology and anthropology. Trays of white clay, shattered and vaguely organized into bins and shapes, resembled bones that had fallen and cracked during an excavation. More colorful murals depicted apothecaries and scenes of biological study. A series of portraits that I thought belonged to the artists turned out to be an ethnographic photography project on decolonizing race and gender. A fishing net full of clothing, fabric, and plastic objects looked like a scoop out of modern consumerism. The piece that touched me the most, however, was a circle of chairs with a rainbow of blankets and hand-made shoes all facing inward. I imagined the fictional people that may belong to those shoes, the diverse family that could be united under a shower of color and patterns. The map is not the territory, I thought of the exhibition’s title. Surely this was the most social representation of that, besides the photography.

The last sculpture I looked at was a dimly glowing monolith. Indistinguishable shapes coming from within the object created curious shadows on its inner walls. I noted in my journal that it resembled “an almost snuffed candle.” It also reminded my of a dying lighthouse, a match on its last flame, or something to lead humanity to the end of the line, past all of the broken fossils and polluted rivers, into somewhere with more light.

The artists were Annette Bellamy, Fernanda D’Agostino, Jenny Irene Miller, Mary Ann Peters, Ryan Pierce, Robert Rhee, Henry Tsang, and Charlene Vickers. The exhibition is open until May 5, 2019. – Sophia Valdez